Jacques, Jack and the Technocrats

A full decade before Jacques Ellul wrote his groundbreaking work, The Technological Society, C. S. Lewis completed the third book of his Space Trilogy, That Hideous Strength. Since Lewis was called Jack by his family and friends, it is interesting that he and Ellul shared a first name rooted in the name Jacob. But they also shared a prescient sense of where applied science and technology would lead modern societies if human-based values were no longer at the helm.

Whereas the first two novels of Lewis’ trilogy involve the prospect of Mars and Venus being colonized by imperialistic scientists, the final novel takes place on Earth, setting the stage for the beginnings of a dystopian society seeded by a group of British technocrats. Lewis was genuinely concerned that other planets, through technological advancements, would be corrupted by adherents of what Lewis knew as Scientism. Arthur C. Clarke, at the time, took great offense to this scenario of corruption; he engaged Lewis in correspondence from 1943 to 1954 (Miller).

Whereas the first two novels of Lewis’ trilogy involve the prospect of Mars and Venus being colonized by imperialistic scientists, the final novel takes place on Earth, setting the stage for the beginnings of a dystopian society seeded by a group of British technocrats. Lewis was genuinely concerned that other planets, through technological advancements, would be corrupted by adherents of what Lewis knew as Scientism. Arthur C. Clarke, at the time, took great offense to this scenario of corruption; he engaged Lewis in correspondence from 1943 to 1954 (Miller).

One interesting feature in the effort toward totalistic control over society, as developed in That Hideous Strength, is the matter of influencing public opinion through the news media. Mark, the insecure protagonist in the story, finds himself drawn into the “inner ring” of the technocratic project; he eventually discerns his role to write stories that support the agenda of the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments (N.I.C.E.).

In a conversation with Hardcastle, head of the institute’s police force, Mark learns about the importance of writing stories prior to the happening of actual events. But how can such a “newspaper stunt” be done, he asks, “without being political? Is it Left or Right papers that are going to print all this rot…?” Hardcastle then instructs him on the necessity of feeding both sides.

Isn’t it absolutely essential to keep a fierce Left and a fierce Right, both on their toes and each terrified of the other?….Any opposition to the N.I.C.E. is represented as a Left racket in the Right papers and a Right racket in the Left papers. If it’s properly done, you get each side outbidding the other in support of us–to refute the enemy slanders. Of course we’re nonpolitical. The real power always is (Hideous, 99).

Mark then questions whether this strategy can work with educated people, to which Hardcastle firmly rebuffs him. “It’s the educated reader who can be gulled….When did you meet a workman who believes the papers? He takes it for granted that they’re all propaganda” (99). Thereafter, the discussion migrates towards the subtle arts of conditioning, and how this, in part, depends on the compulsive nature of high-brow folk keeping up with the latest news.

Let me backup a bit and accent the idea of real power being nonpolitical. In a similar way that Marx understood how the highest form of power is held less by politicians and held more by those who control economies of capital, Ellul posited that ultimate power is rooted in technological systems that encompass all other sub-systems of society, be them economic, political, scientific, or cultural. In Perspectives On Our Age, Ellul explains how our concerns for the political problems of our day (elections, partisanship, democracy, etc.) need to be viewed in a larger context of the “technological milieu” which governs the nature of all political competition.

Political power is now in the hands of technological structures that far surpass any power ever held by older political authorities. However, this is no longer a political problem. Whatever the regime, it has its structures in hand. The problem is actually a technological one (Perspectives, 63).

Ellul then proceeds to explain how the technological system is autonomous (literally, a law unto itself). In short, no other sub-system can intervene from the outside precisely because they are not ‘outside’ but rather already engulfed. He then states how “technology is autonomous to morality.” This does not mean, however, there is no human intervention. “What happens is that the system determines the one who must make the decision and who must act. The sole actions and decisions to be allowed are the ones that promote the growth of technology.” In this context, says Ellul, “only progressive thinking is valid” (Perspectives, 64-5).

These ideas align very well with Lewis’ nonfiction work which forecasted themes developed in Hideous, namely The Abolition of Man. In this short book, Lewis paints a pessimistic view of western civilization where technique-driven society would outpace any moral guidance or critique. In the end, the conquest of nature includes the conquest of human nature, and we end up losing our essential humanity. With Ellul, Lewis feared the loss of universal values (summed up as the Tao), resulting in a world where “the solution is the technique” (Abolition, 88).

These ideas align very well with Lewis’ nonfiction work which forecasted themes developed in Hideous, namely The Abolition of Man. In this short book, Lewis paints a pessimistic view of western civilization where technique-driven society would outpace any moral guidance or critique. In the end, the conquest of nature includes the conquest of human nature, and we end up losing our essential humanity. With Ellul, Lewis feared the loss of universal values (summed up as the Tao), resulting in a world where “the solution is the technique” (Abolition, 88).

Both Jack and Jacques understood how the Conditioners (Lewis’ term) are also conditioned by the mechanical values that stem from their worldview. Moreover, both were also tuned into the higher “principalities and powers” that govern human systems. Marx understood Capital as having a sort of invisible force. Ellul identities these powers as Mammon, Nationalism, Progress, and so forth, all of which are subservient to Technique. Lewis called them Macrobes in Hideous Strength (257).

Lewis writes something that even Karl Marx would have appreciated: “What we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.” This line, as pointed out by Alan Jacobs (Year 1943 – 134,138), is stated verbatim in Hideous by the scientist Filostrato (178). In a later conversation, Mark learns how the dead weight of the human population serves “as a kind of cocoon for Technocratic and Objective Man.” “The human race is to become all Technocracy” (258). (BTW….Jacobs concludes his book with an Afterword about Ellul.)

In closing, new readings of Lewis’ twin books, That Hideous Strength and The Abolition of Man, can serve as a stimulating exercise to understand Ellul’s own prophetic analysis of our modern technocratic era. When Lewis writes a sentence like this: “Each new power won by man is a power over man as well” (Abolition, 71), it is hard not to imagine that he is quoting Ellul. Likewise, Ellul could have penned the scene in which the director of N.I.C.E. explains how “existence is its own justification.” A new development of experimental progress can be “justified by the fact that it is occurring, and it ought to be increased because an increase is taking place” (Hideous, 295).

Both Jack and Jacques had a profound sense of how material and spiritual powers can work together, for ill or for good. When George Orwell critiqued Lewis’ dystopian novel in the Space Trilogy, he wrote that it was unfortunate that “the supernatural (element) keeps breaking in.” Ellul would have noted the irony here. Without diagnosing the spiritual dimensions of institutionally-embedded ‘hideous strengths’, and without having a spiritually-informed prognosis that can thwart the Babel enterprises of today’s world, humanity will ultimately be dominated by non-human forces.

If you haven’t read That Hideous Strength before, I recommend it. I haven’t mentioned how the story ends, but the fact that the title comes from a 16th century poem about the Tower of Babel should provide a clue. I also haven’t mentioned Mark’s wife, Jane, who is equally a protagonist in this story. She, far more than Mark, represents Ellul’s hope for the future. She is drawn into a fellowship of people who truly care about the current drift of new developments, and as people of freedom and responsibility, they rise to the occasion to resist well and turn the tide.

References

Ellul, Jacques. The Technological Society. Knopf, 1964.

Ellul, Jacques. Perspectives on Our Age. Seabury, 1981.

Jacobs, Alan. The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Lewis, C. S. The Abolition of Man. Macmillan, 1943/1947.

Lewis, C. S. That Hideous Strength. Macmillan, 1945/1946.

Miller, Ryder W. From Narnia to a Space Odyssey: The War of Ideas Between Arthur C. Clarke and C.S. Lewis. Simon & Schuster, 2003.

Orwell, George. “The Scientists Take Over,” (Review of C. S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength), Manchester Evening News, 16 August 1945. (Reprinted in The Complete Works of George Orwell, ed. Peter Davison, Vol. XVII (1998), No. 2720 (first half), pp. 250–251.)

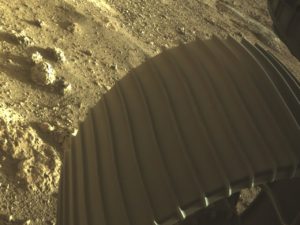

Oh, by the way, Jack, we have just successfully landed a rocket probe on Malacandra. No fears. No sign of colonization yet.