Ellul and Weil

Attention as Waiting: Complementary Critiques in an Age of Technique via Simone Weil and Jacques Ellul

by Sarah Louise MacMillen

We do not attendre…wait.

(Post)moderns are inattentive, therefore, impatient for the revelation of Truth, Justice and Grace.

In place of these values, the logic of what Ellul called “technique” pervades everything.

The writings of Simone Weil and Jacques Ellul include sociological, philosophical, and religious themes, and the two intellectuals serve as “bookends” surrounding the postmodern era. The writers were prolific, respectively, during the time between the World Wars (Weil), and the late 20th century’s Information Age (Ellul). They each dealt with the impact of modernity on humans, further exploring the implications of Weber’s definition of moderns as “sensualists without heart and specialists without spirit.”1

Weil and Ellul had prescient insights on a contemporary trend, namely an unbridled faith in technology, or what Ellul called “technique,” looming large. Ellul and Weil both present a case for how the method of the technological imagination undermines basic needs and obligations for human beings. Alan Jacobs’ text discusses both Weil and Ellul in this light. For Weil the enemy of education is “technocracy…’evil [dominates] wherever the technical side of things is…sovereign.”2 For Ellul, observing later in the 20th century, “education no longer has a humanist…value in itself; it has only one goal, to create technicians.”3 Combining these reflections from the two authors, postmodernity and technique lose touch with what Weil calls “attention”—waiting for God (or Platonist transcendent claims of Truth and Goodness), and also to the human other.4

Weil and Ellul had prescient insights on a contemporary trend, namely an unbridled faith in technology, or what Ellul called “technique,” looming large. Ellul and Weil both present a case for how the method of the technological imagination undermines basic needs and obligations for human beings. Alan Jacobs’ text discusses both Weil and Ellul in this light. For Weil the enemy of education is “technocracy…’evil [dominates] wherever the technical side of things is…sovereign.”2 For Ellul, observing later in the 20th century, “education no longer has a humanist…value in itself; it has only one goal, to create technicians.”3 Combining these reflections from the two authors, postmodernity and technique lose touch with what Weil calls “attention”—waiting for God (or Platonist transcendent claims of Truth and Goodness), and also to the human other.4

The thrust of technique in the contemporary American spheres of social media and education pulls away from critical and reflexive capacities, especially as core values in the liberal arts. These two related spheres of change suggest the unreflective assertion of ideas without in-depth, historical learning, or an ethically entrenched humanistic approach. Higher education and wider communities of discourse reflect an age of empty speech and the worship of technological innovation and “the newest.” This moves away from the charism of St. Bernard of Chartres who reminds us that “New knowledge is always standing on the shoulders of giants.”

The postmodern person expresses ideas on Twitter, blogs, etc., before actually being attentive to the history, context, and contours of the “giants” preceding them. Opinions matter before knowledge or wisdom. Tom Nichols has explored this in his analysis on the death of expertise.5 Today, Ellul’s sense of “technique” could be like a “tech-Gnosticism”— an unwavering faith in both self-expression and its vehicle in the newest technological innovations. This is also backed by the general assumption or expectation of instantaneous material results. The symptoms of technique in the educational sphere are reflected in shrinking liberal arts programs, and in an increasing emphasis on instant payoff, pre-professional degrees, and STEM.

Ellul might look at this vision for the future in educational and media systems as a technique-driven “instrumental rationality”6 among students, faculty, and administrators. Juggernauted by the dominant capitalist worldview, it should rather be a safeguard against it. In philosophic metaphors, it is an embrace of functionaries of the sophistry “inside Plato’s Cave.” One could consider how Weil would call the student (and academic) to a renewed look at the ancient classics, or the allegory of the Cave and “The Great Beast” in this light—perhaps showing how the role of philosophy is a shadow of what it once was.

Ironically, the “Great Beast” of today is not necessarily an “uneducated mob” force (per Plato’s rendering). Today’s figure is more of a diploma’ed middle class, but never quite being a satisfied, hedonistic collection of “sensualists without heart.” The postmodern Zeitgeist might be the impetus of self-serving motivations of educated white-collar bureaucrats. This class of the knowledge industry has a need for constant entertainment, seeking the comfort of goods like consumer items, media input or entertainment bingeing, constant affirmation through social feedback and through social status on media platforms, and unconditional acceptance and recognition rather than the higher Goods of Truth and Justice. This is an example of the cultural historian Christopher Lasch’s concept of postmodernism’s “minimal” self—the contemporary human adoring of the great beast of consumerism and constant feedback.7 Affirming the insights of Alasdair MacIntyre, Lasch highlights the limitless craving and vacuous discourses on self-esteem and psychic survival as additional reflections of the culture of narcissism in bureaucratic societies.8

Simone Weil is critical of this tendency, and brings in a discussion of Plato’s Republic, Book VI. The just person is naturally an outsider, and in tension with these common trends of the society: “To adore the Great Beast is to think and act in conformity with the prejudices and reactions of the multitude to the detriment of all personal search for truth and goodness.”9

Yet the impetus of the technological tendencies in postmodern life diminish relationships in the vortex of “technique” itself as a new central value. Robert Merton’s foreword to Jacques Ellul’s The Technological Society explores Ellul’s contribution to the sphere of social theory. He also affirms the Weberian mode of inquiry and critique: “The technical man is fascinated by results…Above all he is committed to the never-ending search for the ‘one best way’ to achieve any designed objective.”10 In this brief synopsis, Merton illustrates a key focus on “method” in Ellul’s concept of “technical” humanity in modernity. Simone Weil might reflect on contemporary technical life as rather “hasty.” We do not attendre…wait. (Post)moderns are inattentive, therefore, impatient for the revelation of Truth, Justice and Grace. In place of these values, the logic of what Ellul called “technique” pervades everything.

Technique is also a willful force, as Ellul’s classic application of the concept to propaganda illustrates. For Simone Weil, the suspension of willfulness is an important part of the educational process. Yet the very premise of postmodern communication technologies (as they cling to a pedagogical mechanism) suggests not suspension of the will, but the assertion of it within the context of a need for immediate response, entertainment, and instant gratification. It is, by definition, the opposite of waiting. In Gravity and Grace, Weil challenges us to “try to cure our faults by attention and not will.”11 Weil’s ethic of attention moves counter to contemporary technology’s will-to-force persuasion and domination—even beyond the reality at hand into “alternative facts.” This has economic, relational and political implications as well.

Technique is also a willful force, as Ellul’s classic application of the concept to propaganda illustrates. For Simone Weil, the suspension of willfulness is an important part of the educational process. Yet the very premise of postmodern communication technologies (as they cling to a pedagogical mechanism) suggests not suspension of the will, but the assertion of it within the context of a need for immediate response, entertainment, and instant gratification. It is, by definition, the opposite of waiting. In Gravity and Grace, Weil challenges us to “try to cure our faults by attention and not will.”11 Weil’s ethic of attention moves counter to contemporary technology’s will-to-force persuasion and domination—even beyond the reality at hand into “alternative facts.” This has economic, relational and political implications as well.

Robert Merton expands:“Technique transforms ends into means…Technical economic analysis replaces political economy.”12 This involves a major shift away from moral questions of relationships and the consequences of technology within the economic system. In politics: “The technician sees the nation quite differently than the political man… To him the state is not the expression of the will of the people, nor a divine creation nor a creature of class conflict. It is an enterprise providing services that must be made to function efficiently”13

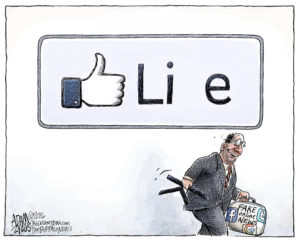

The political application of “technique” implies utility rather than justice. When utility and efficiency drive a state structure, the next thing that is jeopardized is Truth. Propaganda is ubiquitous in the postmodern era. For Ellul, propaganda has two moments. The first is described by Merton: “Restraints on the rule of technique become increasingly tenuous. Public opinion provides no control because it too is largely oriented toward performance.14 In other words, postmodern education emphasizes form over content in communication. The second moment presents the reality that every domain and institution of social life is on the same continuum. Education-Politics-Economics… they all escape into a mode of “technically-dominated media, pop-culture.”15

Truth and Justice: Weil and Ellul

Weil’s philosophy is a force of Truth against the mode of propaganda, and an encounter with our mutual limitations as humans—the spiritual antidote to the abuses of what Ellul defines as technique. In The Need for Roots, Weil argues for a sense of rootedness and democracy before the Truth. This involves small and big truths—against lying, poor grammar structures, or even, corrupt judges.16 Also, in her “Statement of Human Obligations,” Weil defines humans as persevering for the Truth/the Good. “At the center of the human heart is the longing toward the absolute Good…Just as the reality of this world is the sole foundation of facts, so that other reality is the sole foundation of good.” 17

November 18, 2016

How does society orient itself toward the Truth-Good in an age of circular propaganda, “fake news,” and “alternative facts”? The communications scholar Artur Matos-Alves discusses that today, more than ever, Ellul’s concept of “technique” is radically applicable and serves as a critical lens into the uncharted terrains of the Internet, especially social media. Whereas the Frankfurt School described the ways in which propaganda and technology have a vertical structure, Ellul anticipated how the hopes of postmodernization in technological spheres would have democratic aims, but would end up undermining them with a hollowing out of society’s moral center in the erosive quality of instrumental rationality and a stress on efficiency as a principle.18 Modern communications emerged in the setting where technical rationalism combined with the colonizing force of “propaganda.” With a growing base of middle and lower class ressentiment and the anti-politics of frustration (in a newly fashioned lumpenproletariat), media becomes the new opiate. For Ellul, “The technical starting point is the human behavior of the majority.19 This corroborates with Weil’s sense of Plato’s “Great Beast,” as mentioned above.

The Contemporary Domain of Media and Technique

Ellul forebodingly observed an innovation of media and propaganda technics, which is quite relevant to the types of provocation from “news” and other outlets today. Alves discusses how this agitation propaganda seeks to overcome a given situation, and is led by the opposition in order to overthrow its enemies, usually in a revolutionary situation. It is precisely because of human resistance to the modern way of life, in addition to the technological innovations (which lead to certain pockets of unemployment and alienation), that technological societies feed agonistic-agitation propaganda. Technology functions to both agitate, but then soothe the feelings of disconnection, alienation, and anomie. Technology treats a symptom, but it does not alleviate the very circumstances it has brought about in modernity’s domain of technique. Ellul’s theory could today address an ethical critique of the new platforms of social media and “horizontal” or circular propaganda. Examples of this form of media would include posting or responding or forwarding on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, etc.

The reigning principle of production in the context of technique is that of “efficiency.”20 However, the unintended consequences of these new forms of productivity and instant gratification presents an irony in this searching for “enjoyment” in the context of modern life—it produces opiate-like entertainment rather than education. It numbs, entertains, and educates, all the while asking for confession and conformity. To sum up, technique is ultimately a self-perpetuating force, both inner impulsion and outer compulsion, to dominate, work, conform, numb.

Weil’s ethic of attention is precisely the opposite of contemporary technique’s will-to-force in persuasion and domination. In Weil’s vision of a healthy society, intellectuals, teachers (hopefully politicians?) are still humbled by the fact that we cannot obtain complete Wisdom in the Cave/City. In a very Augustinian rendering here, Weil notes: “It is the part played by joy in our studies that makes of them a preparation for spiritual life, for desire directed towards God is the only power capable of raising the soul…desire alone draws God down.”21

Ellul presents a sociological description of the postmodern witness: s/he must wade through the morass of propaganda. Ellul’s questions, specific to a Christian audience, are a) how do we live amidst the mechanisms of technique and its manipulations of knowledge, power, and technology? And, b) what work is necessary to proclaim the Gospel amidst these forces against it? His answer is one of a radical non-violence and anti-power, responding to these elements within postmodern technique.22 Jacques Ellul boldly proclaims the Holy Spirit is the solution to the problems of modernity, involving not just prayer, but action.23 Simone Weil would have us return to an obligation to be “attentive” as a unifying ethic of both a) pedagogy/didactics, and b) being-in-the-world. It is that openness of waiting and hope (attendre et espérer) against the domineering and willful aspect of technique.24 Waiting (attention) suggests a true openness to the experience of others—it is an ethic and discipline of listening in an age of empty speech.

Notes

[1] See Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons; with an introduction by Anthony Giddens. (New York: Routledge Classics, 2001).

[2] Alan Jacobs, The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in a time of Crisis. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 165.

[3] Jacobs, The Year of Our Lord 1943, p. 202.

[4] Simone Weil, “Reflection on the Right Use of School Studies,” in Simone Weil, ed. Eric O. Springsted. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1998), pp. 91-99.

[5] Tom Nichols, The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[6] Max Weber, Max Weber on Charisma and Institution Building. Edited with an introduction by S.N. Eisenstadt. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968).

[7] Christopher Lasch. The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times. (New York: Norton, 1984)

[8] See Alasdair MacIntyre. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

[9] Simone Weil, Simone Weil: An Anthology, ed. Sian Miles. (New York: Grove Press, 1986), p. 121.

[10] Merton, in Jacques Ellul. The Technological Society. With an introduction by Robert K. Merton. (New York: Vintage, 1964), p. vi.

[11] In Simone Weil: An Anthology, p. 211.

[12]In Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society. With an introduction by Robert K. Merton. (New York: Vintage, 1964) p. vii.

[13] Merton, in Ellul, The Technological Society, p. vii.

[14] Ellul, The Technological Society, p. vii.

[15] In Ellul, The Technological Society, viii.

[16] Weil, An Anthology, 119-120.

[17] Weil, An Anthology, 202.

[18] Alves, Artur Matos. “Jacques Ellul’s ‘Anti-Democratic Economy’: Persuading Citizens and Consumers in the Information Society,” Cognition Communication Cooperation 12:1 169-201 (2014), p. 171.

[19] Alves, “Jacques Ellul’s ‘Anti-Democratic’”, p. 171.

[20] Alves, “Jacques Ellul’s ‘Anti-Democratic,’” 196.

[21] Simone Weil, “Reflection on the Right Use of School Studies.”

[22] Jacques Ellul. Essential Spiritual Writings, selected with an introduction by Jacob E. Van Vleet. (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2016), p. 67.

[23] Ellul, Essential Spiritual Writings, pp. 56-57.

[24] Simone Weil, “Reflection on the Right Use of School Studies.”