Sister Society: Association Internationale Jacques Ellul

Sister Society: Association Internationale Jacques Ellul

by Darrell J. Fasching, Professor Emeritus,

Religious Studies, University of South Florida, Tampa

According to Jacques Ellul, a technological society is not one of machines but of techniques. It is a social milieu made up of the sum total of techniques, “rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every area of human endeavor (The Technological Society, xxv).” Following the great French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, Ellul argues that what holds a society together is its sense that it is sacred — and what is sacred is blasphemy to try to change. Humans treat as sacred whatever forms of power they believe govern their society and destiny. Once we humans were totally dependent on nature and struck with awe at the ability to provide for all our needs. Indeed humans engaged in religious ritual to bring themselves into harmony with its demands. Then, as Ellul explained in the The New Demons (1977), science and technology proved themselves powerful enough to desacralize nature and so replaced it as the new sacred powers governing human destiny — a society of techniques or technicist society. Today the technicist society replaces nature as our all-encompassing environment which fills us with utopian hope and awe because of the pleasures and abundance that technique promise.

Whether with nature or technology, humans succumb to a sacral awe of the powers which govern their destiny and rob them of their freedom and capacity for critical reflection. This awe turns them into slaves sacrificing and serving their new idols. A society of techniques undermines human freedom by requiring that we always choose the most rationally efficient techniques for every endeavor. No business or society can afford to choose a less efficient solution for fear of being rendered obsolete by their competitors. Even as once political ritual, in ancient Rome and elsewhere, mediated the divine favors granted by nature’s deities, so today, says Ellul, politics serves the technical myth of utopia by providing the collection of rituals that create the illusion of control over the favors granted by technique. And yet we discover that contemporary political rituals involve holding hearings from technical experts who can advise politicians on the most efficient techniques which can be used to solve our problems. Technical necessity continues to reign while utopian fantasy, Ellul argues, “is a consolation in the face of slavery, and an escape from something one is unable to prevent. . . . Whenever men have taken utopian descriptions seriously, the result has been disastrous” (“Search for an Image,” in Images of the Future, ed., Robert Bundy (Buffalo NY Prometheus Books, 1976) pp. 24-25.)

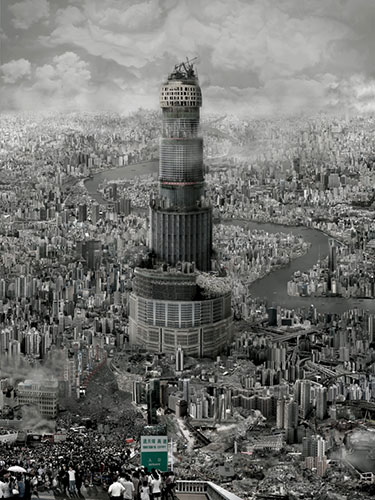

Tower of Babel: Conflict of Laws, ©2010, Du Zhenjun

In such a society, no protest against the efficiency of technique is possible or even desired because we are enthralled with the utopian world of wonders we believe technique can give us. Moreover, all discontent is treated with psychological and sociological therapeutic and mass media techniques that will help us become well adjusted, fully entertained and happy with our slavery. Utopian hopes integrate the individual into the necessities of a technological society. Their promise: accept the demands of efficiency and your fondest hopes for wealth, pleasure and abundance will be fulfilled, offering a heaven on earth.

For Ellul, as long as humans place all their hope in this technical society there is no possibility of freedom or revolt against its necessities — only the useless therapeutic revolt that allows us to protest by letting off steam by lunging at TV screens so as to be covered by the evening news. This creates the illusion of media driven politics; namely that we are being heard and changing things while actually we are being reconciled to our fate.

The only possibility of freedom and revolution depends on humans finding a hope in something beyond the technical system — and that is exactly what the Gospel message offers. It offers, says Ellul, “apocalyptic hope” which breaks with the order of this world through its hope in the God who is Wholly Other than the sacral world of technique. Ordinary hope, hope in the utopianism of the technical future, only short circuits our capacity for revolution. Those with such hopes do nothing. Only a hope offered where there is no hope, only apocalyptic hope anchored in something wholly other than our technical society can bring revolution.

Paradoxically, Ellul sees a possibility in “revolution” that he almost fails to see for “utopia.” Here is the paradox. Ellul, who has spoken just as critically about “revolution” as for “utopia” and yet he does not see this hope for revolution as something to be rejected but something to be “rehabilitated.” Ellul speaks of the need for Christians to participate in every revolution, not in order to tell revolutionaries that they are deluded but in order to help them give birth to their hopes for freedom (To Will and To Do, p. 81) by desacralizing and rehabilitating the sacred. Revolution is a reverse image of the holy, he says, one that has been co-opted by the sacred but its desire for freedom is genuine. However, revolution can only deliver when it is desacralized so as to create a genuine instance freedom as intended by God. When the new demons of the sacred have been exorcised the city becomes sanctified and “Babel is restored to the status of a simple city, and this city becomes the city of the living God” (The Meaning of the City, p. 71. Also, for the ethics of desacralization, see my essay, The Sacred, the Secular and the Holy in the Ellul Forum, April 2014.) And that is the message Ellul finds most powerfully in the Book of Revelation. But one has to ask: given that “utopia,” like “revolution,” has fallen under the influence of the sacred why can’t utopia also be rehabilitated? When Christians participate in and desacralize revolution, they place the human city on a utopian trajectory as an anticipation of the City of God and so help others (non-Christians) to give birth their hopes (see Chapter 7 of my book, The Thought of Jacques Ellul, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1981).

Tower of Babel: The Accident, ©2010, Du Zhenjun

The Apocalyse, or Book of Revelation, brings the message of God’s judgment and transformation of the created order. The biblical notion of creation is one of separation: According to Genesis, God creates by separating light from darkness, heaven from earth, etc. (See Ellul’s, Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation, NY:Seabury Press, 1977) Human sin tries to reverse creation by integrating humans into a seamless order independent of God which only creates tyranny, chaos and destruction. In the Book of Revelation we see God overcoming the chaos of human sin by a series of judgments that separate humans from the demonic powers that seduce humans into a sacral awe, an awe leading to surrender and integration into an order of slavery, sin and death.

Apocalyptic hope is a hope in the One who is Wholly Other than this world and its seductions — the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The God who, as Jesus said, comes to bring not peace but the sword (Matthew 10: 34) — the sword that separates humans from the demonic powers that seduce them and enslave them to sin and its necessities. For Paul, nature is not our fate as the Stoics declared but expresses the utopianism of God’s creation in which the whole of creation is groaning and giving birth to a new creation (Romans 22:22ff ).

Through an intense dialogue with his friend and colleague, Gabriel Vahanian, Ellul modified his position on “utopia” to align it more closely with his position on “revolution” (Gabriel Vahanian, God and Utopia: The Church in a Technological Civilization, Seabury Press, 1977). In his 1977 dust jacket endorsement of God and Utopia, Ellul says, “Gabriel Vahanian is in my opinion a true theologian, one who seeks the best expression for today of the truths of revelation , a man who goes directly to the center of the most decisive issues…. I wonder if he is not one of the very rare genuine contemporary theologians — perhaps the only one…”

Although Ellul strongly objected to the popular utopianism of technological enthusiasts who naively and uncritically embraced technology, in his later work, Ellul’s position became more nuanced. It is no longer “utopia” but the popular distortion of utopia that is problematic. And so Ellul came to affirm that “utopia” has a biblical dimension and belongs “to the order of truth . . . known and created by the word” rather than being just an image and as such can enter into and transform “the order of reality” (The Humiliation of the Word, Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1985, p. 230). Thus when the ideology of technical utopianism is desacralized, just as with “revolution,” its true utopian direction is opened up, making the human city an anticipation of the city of God, where the freedom of the Word of God reigns all in all.