Sister Society: Association Internationale Jacques Ellul

Sister Society: Association Internationale Jacques Ellul

Summaries by Christian Roy (View C. Roy’s webpage on Charbonneau)

Teilhard de Chardin, prophète d’un âge totalitaire

Teilhard de Chardin, prophète d’un âge totalitaire(Teilhard de Chardin, Prophet of a Totalitarian Age). Paris: Denoël, 1963 (re-issued 1981). Downloadable at https://ia600308.us.archive.

A rare critical voice amidst the posthumous vogue of the Jesuit paleontologist and his technophile theodicy —making Christ the Omega Point of the emergent collective mind of evolution as Progress, Charbonneau’s deconstruction of this seductively pseudo-Christian and falsely humanistic ideology is a still potent, scathing indictment of the patron saint of today’s Transhumanist movement, that can help expose the latter’s disturbing implications.

Le paradoxe de la culture

Le paradoxe de la culture(The Paradox of Culture). Paris: Denoël, 1965. Later updated and integrated into Nuit et jour, see below.

Dimanche et lundi

Dimanche et lundi(Sunday and Monday). Paris: Denoël, 1966.

Work and leisure as complementary modern categories into which human life is fitted to suit industrial society’s productivist imperative of total organization.

Célébration du coq

Célébration du coq(Celebration of the Rooster). Le Jas: Robert Morel, 1966. (pdf reprint: https://www.fenixx.fr, 2019).

Charbonneau gives a free rein to his mordant wit in this satire of French nationalism, and by extension, of every local variant of this universal blight of sentimentalized State-worship.

(Motoman). Paris: Denoël, 1967, re-issued 2003.

Mass-man driven by the car, not the other way around, illustrating how the mirage of individual freedom is built into the total mobilization of society by Technique. Even world wars have not made as many victims as the automobile, nor as fundamentally redefined all aspects of life, as Charbonneau shows in this biting critique of car culture. The changes it wrought in his native Bordeaux, palpable in daily life but which no media would touch as such in his lifetime, first alerted him as a teenager to the insidious dictatorship of Change for its own sake in industrial society.

Le Jardin de Babylone

Le Jardin de Babylone(The Garden of Babylon). Paris: Gallimard, 1969; Paris: Éditions de l’Encyclopédie des nuisances, 2002.

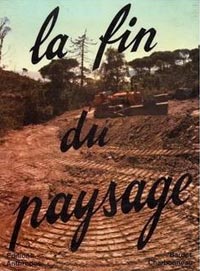

La fin du paysage

La fin du paysage(The End of the Landscape), with Maurice Bardet: foreword and chapter introductions by BC (reissued separately as Vers la banlieue totale, see below). Photos and captions by MB. Paris: Anthropos, 1972.

A picture album of the French landscape in the process of degradation by “development”.

Prométhée réenchaîné

Prométhée réenchaîné(Prometheus Rebound), mimeographed by the author, 1972; Paris: La Table ronde, “La petite Vermillon” series, 2001.

An anatomy of Revolution and its repeated failures, written in the aftermath of May 1968.

(System and Chaos. A Critique of Exponential Development). Paris: Anthropos, 1973; Paris: Economica, “Classiques des Sciences sociales” series, 1990; Paris: Le sang de la Terre, “La pensée écologique” series, 2012; Paris: R & N, foreword by Renaud Garcia, 2022.

The first full statement of the impossibility of infinite growth in a finite world, and the vicious cycle of totalizing system and chaotic breakdown this mirage generates on the road to global technocratic dictatorship and/or planetary environmental collapse.

(Vanishing Countryside). Paris: Denoël, 1973; Paris: Le pas de côté, 2013.

Ironically echoing structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes tropiques that made concern over the plight of distant tribes fashionable, Charbonneau tries to get the French to pay attention to the tragedy of a disappearing traditional society on their own doorstep: that of the Béarn countryside where he chose to settle. (Wendell Berry comes to mind…)

Notre table rase

Notre table rase(Meagre Pickings.) Paris: Denoël, 1974, downloadable at https://archive.org/details/

The literal tabula rasa of what passes for food in industrial society.

(The Ecologists), with Pierre Samuel. Paris: Marabout, “Flash actualité” series, 1977.

An introduction to the fledgling environmental movement in French politics. (If anyone locates a cover image, please send to ellulsociety at gmail.com)

(The Green Light. A Self-Critique of the Ecological Movement). Paris: Karthala, “Poing d’interrogation” series, 1980; Lyon: Parangon, “L’Après-développement” series, with a series foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle, 2009; Paris: L’échappée, foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle, 2022.

A critical look back at the early years of the environmental movement and its deep roots in Christian (especially Protestant) culture, with the underlying issues of the relationship of nature and freedom, and of their needful but uneasy joining against the totalizing system of technological society that threatens them both. Using this paradoxical tension as a yardstick, Charbonneau probes the ways in which concepts of Nature have developed as industrialization became second nature and jeopardized the original, taken for granted until its advent. This allows Charbonneau to explain how movements and policies claiming to deal with this issue have gone wrong. English translation by Christian Roy, with a foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle and an introduction by Piers. H. G. Stephens, London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

(I Was. An Essay on Freedom). Self-published, Pau: 1980; Bordeaux: Opales, foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle, 2000; Paris: R & N, 2021.

Man as a being who craves for freedom and yet cannot bear it as it is, i.e. the tension-fraught unity of the spirit and the flesh in a contingent mortal existence. He will thus grasp at every conceivable justification to be relieved of the anxiety this awareness brings, as long as he can convince himself he does it freely, even to achieve freedom. Society usually provides ready-made outlets for this impulse, but individual forms of escapism are not spared either in Bernard Charbonneau’s personal call on each reader to join him in the tragic experience of conscious, embodied freedom, which he considered the summation of his life’s lonely journey against every current of modern society.

Une Seconde Nature

Une Seconde Nature(A Second Nature). Self-published, Pau: 1981; Paris: Le sang de la Terre, “La pensée écologique” series, foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle, 2012.

Aphorisms around the theme of man’s ambiguous relation to society as his second nature, shielding him from the first one at the price of his own freedom.

(The State, first self-published in 1949.) Paris: Economica, “Classiques des Sciences sociales” series, 1987, 1999. Paris: R & N, 2020.

Bernard Charbonneau felt the fetish of the State was such a pervasive hindrance to all critical thought and constructive action that, insisting on tackling it himself, he delegated to Ellul the task of writing the book on his own discovery of Technique. As a kind of historical and theoretical counterpart of Orwell’s 1984, written at the same time, L’État still had to wait forty years to find a proper publisher, despite Ellul’s best efforts to promote it when it first came out as one of Charbonneau’s many samizdats, only available on demand from the author.

Nuit et jour. Science et culture

Nuit et jour. Science et culture(Night and Day. Science and Culture). Paris: Economica, “Classiques des Sciences sociales” series, 1991.

The Paradox of Culture (1965, see above) as a “creative” alibi for the “serious” business of Science as modern society’s Ultima Ratio (written by 1986), in a coupling of works that shows them to be two sides of the same coin.

Sauver nos régions. Écologie, régionalisme et sociétés locales

Sauver nos régions. Écologie, régionalisme et sociétés locales(Saving Our Regions. Ecology, Regionalism and Local Societies). Paris: Le Sang de la terre, “Les dossiers de l’écologie” series, 1991.

Originally titled La planète et le canton (Planet and Township), this book explores the existential connection between the local and the global that defines political ecology as a social project.

Il court, il court, le fric

Il court, il court, le fric(Money Makes the World Go Round). Bordeaux: Opales, 1996.

Charbonneau’s 1980s take on this theme to which Ellul also devoted his 1954 book L’Homme et l’argent (Money and Power).

Un festin pour Tantale. Nourriture et société industrielle

Un festin pour Tantale. Nourriture et société industrielle(A Feast for Tantalus. Food and Industrial Society). Paris: Le Sang de la terre, “Saveurs de la terre” series, 1997; Paris: Le sang de la Terre, “La pensée écologique” series, 2011; foreword by Michel Onfray.

When tasteless, homogenized artificial nutrients become the industrial norm, healthy, varied “organic” food becomes a specialty luxury, part of the very system that makes it a scarce product.

Comment ne pas penser

Comment ne pas penser(How to Avoid Thinking). Written in the 1980s. Bordeaux: Opales, 2004.

Irony as the last resort of thought at the height of seriousness. “These pages were born of the failure to communicate the essence of a life devoted to the creative debate between the individual and his society.”

Bien aimer sa maman

Bien aimer sa maman(How to Love your Mummy). Bordeaux: Opales, 2006.

A humorous look at modern Society as the individual’s Mother-Goddess, with the underlying structures (the State, the Economy, Science, Culture, etc.) that give her enduring identity under the guise of constant change.

Finis Terrae

Finis Terrae(Land’s End, written in the mid-1980s, with a 1990s afterword by the author.) Paris: À plus d’un titre, “La ligne d’horizon” series, foreword by Didier Laurencin, 2010.

The modern conquest of space and time increasingly fills up every corner and every moment of a finite world, depriving us of any meaningful experience of them. (A translation of the first fifty pages by David Bade and Christian Roy is available as a sample, e.g., for potential publishers.)

Le Changement

Le Changement(Change, completed in 1990). Paris: Le Pas de côté, 2013.

The industrial world as an endless, boundless, aimless construction site, as inhospitable to life as a war zone.

Nous sommes des révolutionnaires malgré nous. Textes pionniers de l’écologie politique

Nous sommes des révolutionnaires malgré nous. Textes pionniers de l’écologie politique(We Are Revolutionaries in Spite of Ourselves. Pioneering Texts of Political Ecology), with Jacques Ellul. Paris: Le Seuil, “Anthropocène” series, introduction by Quentin Hardy, with critical notes by Christian Roy, 2014.

This is a collection of four early texts from the time of the close collaboration of Bernard Charbonneau and Jacques Ellul as leaders of a regional branch of the Personalist movement in Southwestern France, to which they gave their unique technocritical stamp, likely making it the world’s first recognizable example of political ecology as a revolutionary movement in its own right beyond Right and Left, as shown in a fine historical introduction. It starts with the only known overtly text co-authored by Charbonneau and Ellul, “Guidelines for a Personalist Manifesto” (1935, already published as Directives pour un manifeste personnaliste in Cahiers Jacques-Ellul no 1, “Les années personnalistes”, 2004, pp. 63-79), followed by three dazzlingly prophetic Charbonneau texts: “Progress against Man” (“Le Progrès contre l’Homme”, 1936), “Feeling for Nature as a revolutionary force” (“Le sentiment de la Nature, force révolutionnaire”, 1937) and “The Year 2000” (“An deux mille”, 1945, on the implications of the A-bomb), the latter available online in an English translation by Louis Cancelmi at https://www.signals-noise.com/2017/03/17/bernard-charbonneau-political-ecology/

Lexique du verbe quotidien

Lexique du verbe quotidien(Lexicon of Everyday Speech.) Geneva: Héros-Limite, “Feuilles d’herbe” series; foreword by Alexandre Chollier, 2016.

A collection of long-form columns arranged in word entries that first appeared in the Protestant weekly Réforme in the 1950s, containing early formulations of many of the themes Bernard Charbonneau would go on to develop in his books in subsequent decades.

L’Homme en son temps et en son lieu

L’Homme en son temps et en son lieu(Man in His Time and Place.) Paris: R & N, “Ars Longa Vita Brevis” series; foreword by Jean Bernard-Maugiron, 2017.

In this brief text written in 1960, Bernard Charbonneau examines the vital role of time and place in enabling or hampering human freedom, in an era when technology fractures and shrivels them.

Quatre témoins de la liberté (Montaigne, Rousseau, Berdiaeff, Dostoïevski)

Quatre témoins de la liberté (Montaigne, Rousseau, Berdiaeff, Dostoïevski)(Four Witnesses to Freedom: Montaigne, Rousseau, Berdiaeff, Dostoevsky). Paris: R & N, “Ars Longa Vita Brevis” series, with a foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle, 2018.

Bernard Charbonneau’s testament on freedom as the lodestar of his thought, revisited in his final years through the prism of four authors who helped him articulate aspects of this common theme.

Vers la banlieue totale

Vers la banlieue totale(Towards Total Sprawl). Paris: Eterotopia, “Rhizome” series, 2018.

A separate reissue of Charbonneau’s essays accompanying sections of the photo book La fin du paysage published with Maurice Bardet in 1972 (see above).

Le totalitarisme industriel

Le totalitarisme industriel(Industrial Totalitarianism.) Paris: L’Échappée, “Le pas de côté” series, foreword by Pierre Thiesset, 2018.

A collection of Bernard Charbonneau’s column “Chroniques du terrain vague” (“Chronicles of the vacant lot”) for La Gueule ouverte between 1972 and 1977 and of articles published in Combat nature from 1974 to his death in 1996, that made him a respected radical voice in the French ecological movement he pioneered and steadfastly championed.

La nature du combat : pour une révolution écologique

La nature du combat : pour une révolution écologique(The Nature of the Struggle: For an Ecological Revolution.), with Jacques Ellul. Paris: L’Échappée, “Le pas de côté” series, foreword by Frédéric Rognon, afterword by Pierre Thiesset, 2021.

A collection of articles by Bernard Charbonneau and Jacques Ellul for the ecological review Combat nature (1974-2004).

La Société médiatisée

La Société médiatisée(Mediatized Society, self-published in 1986.) Paris: R & N, foreword by André Vitalis, afterword by Christian Roy. Serialized English translation in progress on the dedicated crowdfunding site https://www.patreon.com/christianroymedia.

Charbonneau’s reflection on media owed much to the bitter experience of being ignored by Technological/Mediatized Society for dealing with its mechanisms as such rather than taking sides in dominant discourses about current affairs, under cover of which it reshapes human reality unimpeded. Such immediate and profound change does not even count as news for the media that screen out any serious discussion of it, tacitly justifying it instead of informing the public about its implications so people could form their own judgment. “The media are blind to the daily realities that come back every day. They need new stuff, instantly forgotten in favour of some other new thing.”(52-53) This is the law of the scoop that governs “information-publicity-propaganda” as a single set of phenomena, which gives its title to the second part of La Société médiatisée, fulfilling the transition “from speech to its industrial reproduction” covered in the first part. What this leads to in the third part is the “manufacturing of an antireality”, besides which Corporate or State censorship is secondary: for the censorship of a Third Power—the Media—is automatic, beyond the awareness of those who experience it or who exert it, as we now know too well as willing pawns of data algorithms. In a final part, Charbonneau asks: “Well then, what is to be done?”, and gives some cues.

La Propriété c’est l’envol. Essai sur la bonne et la mauvaise propriété.

La Propriété c’est l’envol. Essai sur la bonne et la mauvaise propriété.(Property is Heft. An Essay on Good and Bad Property, self-published 1984.) Paris: R & N, foreword by Daniel Cérézuelle: “At once means and obstacle, it would be just as unrealistic to want to eliminate property as it would be immoral to sacralize it. But this book entreats us not to let ourselves be caught in abstract alternatives. For or against property? We first need to know what property we mean, within which limits, and in what context.”

Bernard Charbonneau published a great many articles in several periodicals, starting with those of the Personalist movement, contributing a few important articles (e.g. on advertising and on education) to its main review Esprit, but, along with Ellul, mostly writing much of the material of tiny-circulation internal newsletters of its regional branches in Southwestern France, where most of their key ideas were first articulated. After the war, Ellul would be instrumental in giving Charbonneau access to Protestant publications, such as the student journal Le Semeur to which he occasionally contributed from 1945 to the 1980s, and especially the weekly Réforme from 1950 to the early 1960s, where the topics of their respective books were often first sketched —even those of one by the other in some cases! After getting a second wind as an elder statesman of the environmental movement of the 1970s, Charbonneau had a regular column in La Gueule ouverte (The Gaping Mouth), an appropriately irreverent ecological spin-off of the satirical paper Charlie-Hebdo, from 1972 to 1977, and would also contribute to the regional newspaper La République des Pyrénées from 1977 to 1983, as well as to the environmentalist review Combat Nature from 1974 to his death in 1996. In the early 1990s, at the instigation of Christian Roy, Charbonneau also contributed to special issues of the Montreal-based trilingual “transcultural magazine” Vice Versa on the themes of nature, work, and media.

Bernard Charbonneau published a great many articles in several periodicals, starting with those of the Personalist movement, contributing a few important articles (e.g. on advertising and on education) to its main review Esprit, but, along with Ellul, mostly writing much of the material of tiny-circulation internal newsletters of its regional branches in Southwestern France, where most of their key ideas were first articulated. After the war, Ellul would be instrumental in giving Charbonneau access to Protestant publications, such as the student journal Le Semeur to which he occasionally contributed from 1945 to the 1980s, and especially the weekly Réforme from 1950 to the early 1960s, where the topics of their respective books were often first sketched —even those of one by the other in some cases! After getting a second wind as an elder statesman of the environmental movement of the 1970s, Charbonneau had a regular column in La Gueule ouverte (The Gaping Mouth), an appropriately irreverent ecological spin-off of the satirical paper Charlie-Hebdo, from 1972 to 1977, and would also contribute to the regional newspaper La République des Pyrénées from 1977 to 1983, as well as to the environmentalist review Combat Nature from 1974 to his death in 1996. In the early 1990s, at the instigation of Christian Roy, Charbonneau also contributed to special issues of the Montreal-based trilingual “transcultural magazine” Vice Versa on the themes of nature, work, and media.

The go-to source for a steady supply of materials by and about Bernard Charbonneau is Jean Bernard-Maugiron’s website https://lagrandemue.wordpress.com/. (It is named after Charbonneau’s central concept of the Grande Mue, anticipating recent acknowledgments of the Anthropocene era as that of the Great Moulting of the human species, emancipated from nature’s constant pressure only to succumb to a “second nature” of its own making: totalized society.)

The go-to source for a steady supply of materials by and about Bernard Charbonneau is Jean Bernard-Maugiron’s website https://lagrandemue.wordpress.com/. (It is named after Charbonneau’s central concept of the Grande Mue, anticipating recent acknowledgments of the Anthropocene era as that of the Great Moulting of the human species, emancipated from nature’s constant pressure only to succumb to a “second nature” of its own making: totalized society.)

A fairly complete list of Bernard Charbonneau’s articles, compiled by Roland de Miller, appeared at the end of the proceedings of the first conference devoted to him in Toulouse a few weeks after his death: Jacques Prades, ed. Bernard Charbonneau une vie entière à dénoncer la grande imposture. Ramonville: Érès, “Socio-économie” series, 1997.

The proceedings of a more recent conference on Charbonneau in Bordeaux in 2019 have also been published: Florence Louis, ed. Résister au totalitarisme industriel: Actualité de la pensée de Bernard Charbonneau. Paris: R & N, 2022.

The proceedings of a more recent conference on Charbonneau in Bordeaux in 2019 have also been published: Florence Louis, ed. Résister au totalitarisme industriel: Actualité de la pensée de Bernard Charbonneau. Paris: R & N, 2022.

A subsequent conference on Charbonneau and Ellul took place in Strasbourg in 2021: Frédéric Rognon & Jacob Marques Rollison, eds. Face aux défis écologiques et technologiques. L’éthique de Bernard Charbonneau et Jacques Ellul. Paris: R & N, 2024.

While we await the publication of Sébastien Morillon-Brière’s capacious dissertation on Bernard Charbonneau, the only monograph on his life and thought remains the following:

Daniel Cérézuelle, Écologie et liberté. Bernard Charbonneau : précurseur de l’écologie politique. Lyon: Parangon/Vs, “L’Après-développement” series, 2006; reissued as Nature et liberté : introduction à la pensée de Bernard Charbonneau. Paris: L’Échappée, 2022.

Daniel Cérézuelle, Écologie et liberté. Bernard Charbonneau : précurseur de l’écologie politique. Lyon: Parangon/Vs, “L’Après-développement” series, 2006; reissued as Nature et liberté : introduction à la pensée de Bernard Charbonneau. Paris: L’Échappée, 2022.

For a pocket-size survey and anthology, see: Daniel Cérézuelle, Bernard Charbonneau ou la critique du développement exponentiel. Paris : Le passager clandestin, “Les Précurseurs de la décroissance” series (Serge Latouche, ed.), 2018.

Daniel Cérézuelle, “Critique de la modernité chez Charbonneau”, in Patrick Troude-Chastenet, ed., Sur Jacques Ellul. Le Bouscat: L’Esprit du temps, 1994, pp. 61-74.

Christian Roy, “Aux sources de l’écologie politique : le personnalisme gascon de Bernard Charbonneau et Jacques Ellul”, Canadian Journal of History / Annales canadiennes d’histoire, XXVII, April 1992, pp. 67-100.

Christian Roy, “Ecological Personalism: The Bordeaux School of Bernard Charbonneau and Jacques Ellul”, in Ethical Perspectives (organ of the European Ethics Network), vol. VI, no 1, April 1999, pp. 33-44 (summarized as document no. 698481 in Vol. 36 of The Philosopher’s Index, 2003), available online as a pdf at Ethical Perspectives.

Christian Roy, “Bernard Charbonneau’s Ecological Reflection on Violence and War in Society, the State and Revolution”, in The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence, Vol. IV, Issue 2/2020, pp. 158-176, https://trivent-publishing.eu/img/cms/9-%20Christian%20Roy_full.pdf.

Christian Roy, “Technological Society as Mediatized Society: An Introduction to Bernard Charbonneau’s Media Critique in its Bordeaux School Context”, in New Explorations, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring 2022), pp. 113-128, https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj/article/view/37381/28670.

Patrick Troude-Chastenet, “Bernard Charbonneau : Génie méconnu ou faux prophète?”, Revue Internationale de Politique Comparée, Vol. 4, No. 1, May 1997, pp.189-207.

“Ecological Personalism: The Bordeaux School of Bernard Charbonneau and Jacques Ellul”, in Ethical Perspectives (organ of the European Ethics Network), vol. VI, no 1, April 1999, pp. 33-44 (summarized as document no. 698481 in Vol. 36 of The Philosopher’s Index, 2003), available online as a pdf at Ethical Perspectives.

View https://roychristian.academia.edu

-“The Work of Bernard Charbonneau with Christian Roy”, November 11, 2020, https://podtail.com/podcast/hermitix/the-work-of-bernard-charbonneau-with-christian-roy/

-View a Bernard Charbonneau Zoom Salon between Gerry Fialka, Christian Roy, Piers Stephens and David Bade, March 7, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?

This French website “dedicated to the thought of Bernard Charbonneau” is a treasure trove of texts by and about him.